Posted by Christina Roberts on December 7, 2020.

Introduction

My suggested toolkit about Knowledge Infrastructures is inspired by reading, thinking and research conducted during the Fall 2020 English 238 Critical Infrastructure Studies class. The class was taught synchronously on Zoom by Distinguished Professor Alan Liu of the UCSB English Department.

Professor Liu described the purpose of the class and provided a snapshot of the various types of infrastructural forms to be considered. He wrote, ” This course explores the hypothesis that critical infrastructure studies is one of today’s renewed forms of cultural criticism and media theory. Looking at the world from the point of view of infrastructure — and of the people (and creatures) who at once shape and are shaped by infrastructure — allows us to ask different questions than those posed in the frame of “culture” or “media.” We’ll think broadly about the things, platforms, passageways, containers, and gates — material, mediated, and symbolic — that structure who we are in relation to the world and each other.”

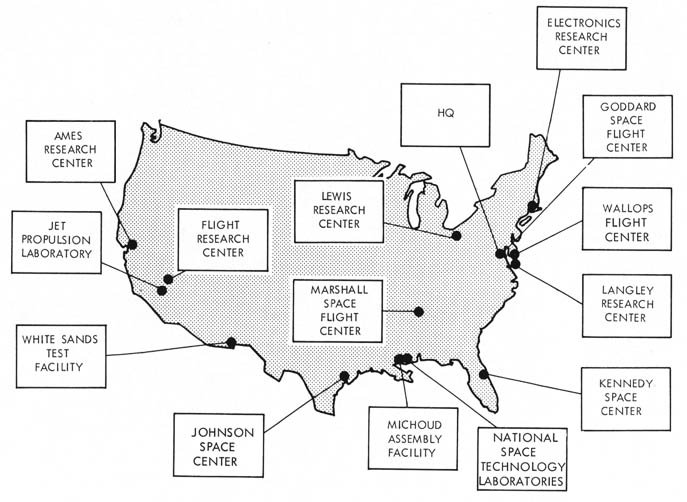

One of the things we learned about the field of Critical Infrastructure Studies is that more historical cases are needed. As an historian-in-training my toolkit is historically grounded. Even though much of the Critical Infrastructure Studies literature is about recent transitions from bricks and mortar to virtual infrastructures, I use the theory of Knowledge Infrastructures to help organize and describe my historical research project about the National Aerospace and Space Administration’s (NASA’s) traveling science education program, the Spacemobile, c. 1961-2015. See my blog for more information.

The Research Problem

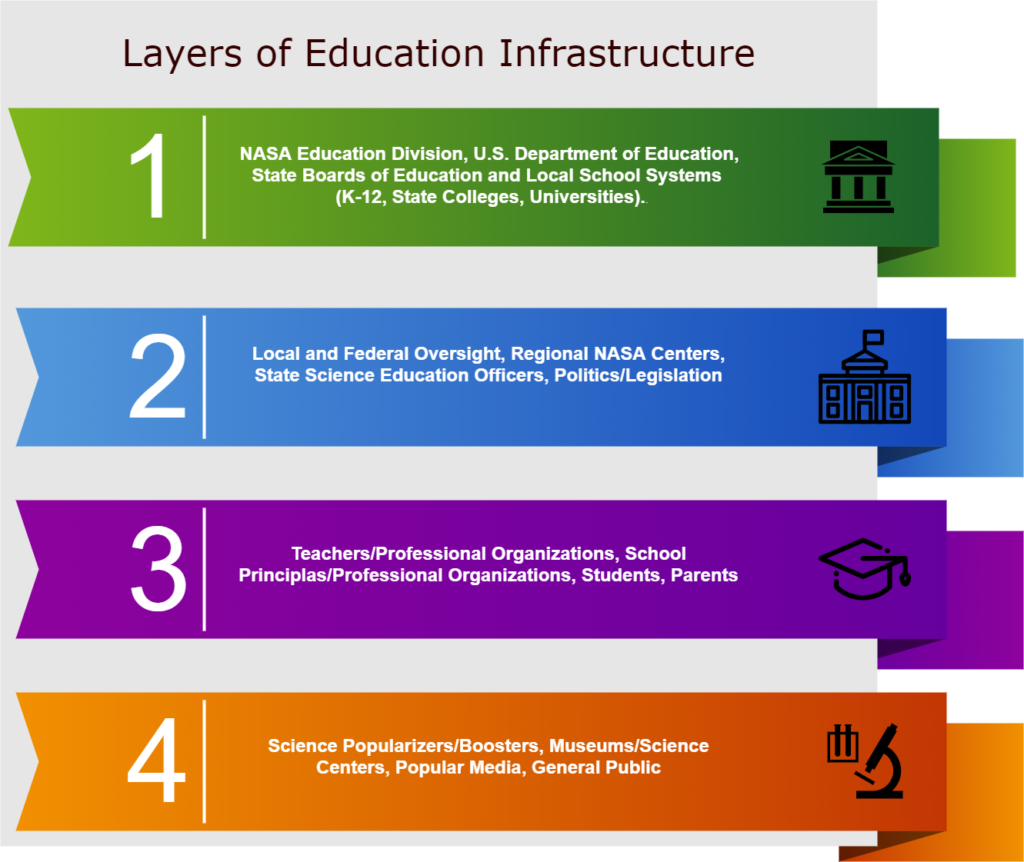

The issue with a highly decentralized organization such as NASA, when paired with the decentralized social function of public education, is that it is hard to get a comprehensive overview of how it all worked. To date, I have identified at least four layers of networked interest groups involved in the history of NASA’s Spacemobile program. From a historical perspective any one of the groups would be a rich subject to explore. But the fact is, the Spacemobile program represents the crossroads where they met to increase and improve science education during the 1960s.

It is clear to me that what was at stake in this historical time period was the distribution and reception of new scientific knowledge produced, facilitated and shepherded by many affinity groups. The theory of Knowledge Infrastructures is therefore an excellent organizing tool for my research.

Knowledge Infrastructures

The key source for conceptualizing Knowledge Infrastructures is Edwards, et. al. (2013), who suggest that Knowledge Infrastructures are robust networks of people, artifacts, and institutions that generate, share and maintain specific knowledge about the human and natural worlds. They include individuals organizations, routines and shared norms and practices. The historical background of information distribution (cyberinfrastructure) is discussed briefly in Bowker, et. al. (2010) and Downey (2002) provides a historical example of information distribution via the telegraph system.

Bowker, G. C., P. N. Edwards, and S. J. Jackson. “The Long Now of Cyberinfrastructure.” In World Wide Research: Reshaping the Sciences and Humanities. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010.

Downey, G. Telegraph Messenger Boys: Labor, Technology and Geography, 1850-1950. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Edwards, Paul N., Steven J. Jackson, Melissa K. Chalmers, Geoffrey C. Bowker, Christine L. Borgman, David Ribes, Matt Burton, and Scout Calvert. 2013. “Knowledge Infrastructures: Intellectual Frameworks and Research Challenges”. Deepblue.Lib.Umich.Edu. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/20

Sociology of Public Demonstration

Rosental (2013) is the key conceptual source for the sociology of public demonstration in that democracies use public demonstrations to manage or direct public affairs related to science. Laurent (2011) identifies “technologies of democracy” that organize public participation in science with the goal of treating public problems. Shapin and Shaffer (2011) provide a classic case study of historical debates over demonstration and experimentation in the history of science.

Laurent, Brice. “Technologies of Democracy: Experiments and Demonstrations.” Science and Engineering Ethics 17, no. 4 (2011), 649-666. doi:10.1007/s11948-011-9303-1.

Rosental, Claude. “Toward a Sociology of Public Demonstrations.” Sociological Theory 31, no. 4 (2013), 343-365. doi:10.1177/0735275113513454.

Shapin, Steven, and Simon Schaffer. Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

The Idiom of Co-Production

Jasanoff (2004) is a key source for conceptualizing co-production of the natural and social orders with respect to science and technology. Dennis (2004) provides a science history case study of co-production from the mid-twentieth century and Byrnes (1994) provides a classic example of NASA shaping the political order and in turn being shaped by it.

Byrnes, Mark E. Politics and Space: Image Making by NASA. Santa Barbara: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994

Dennis, Michael Aaron. “Reconstructing sociotechnical order: Vannevar Bush and US Science policy.” In States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order. London: Routledge, 2004.

Jasanoff, Sheila. States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order. London: Routledge, 2004.

The Stack

Lastly, I include a nod to the concept of The Stack. Even though I do not discuss internet infrastructures in my project, the layered modularity of The Stack evocatively instructs my perception of the layers of science education infrastructure that supported and interfaced with the Spacemobile program. Some instrumental quotes from Bratton:

“Stacks are a kind of platform that also happens to be structured through vertical interoperable layers, both hard and soft, global and local. Its properties are generic, extensible, and pliable; it provides modular recombinancy but only within the bounded set of its synthetic planes…”. (52)

“Paths between layers are sutured by specific protocols for sending and receiving information to each other, up and down, that do the work of translating between unlike technologies gathered at each plateau. In this sense, each layer can then simulate and countersimulate the operations of the other…”. (67-68)

Bratton, Benjamin H. The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016.

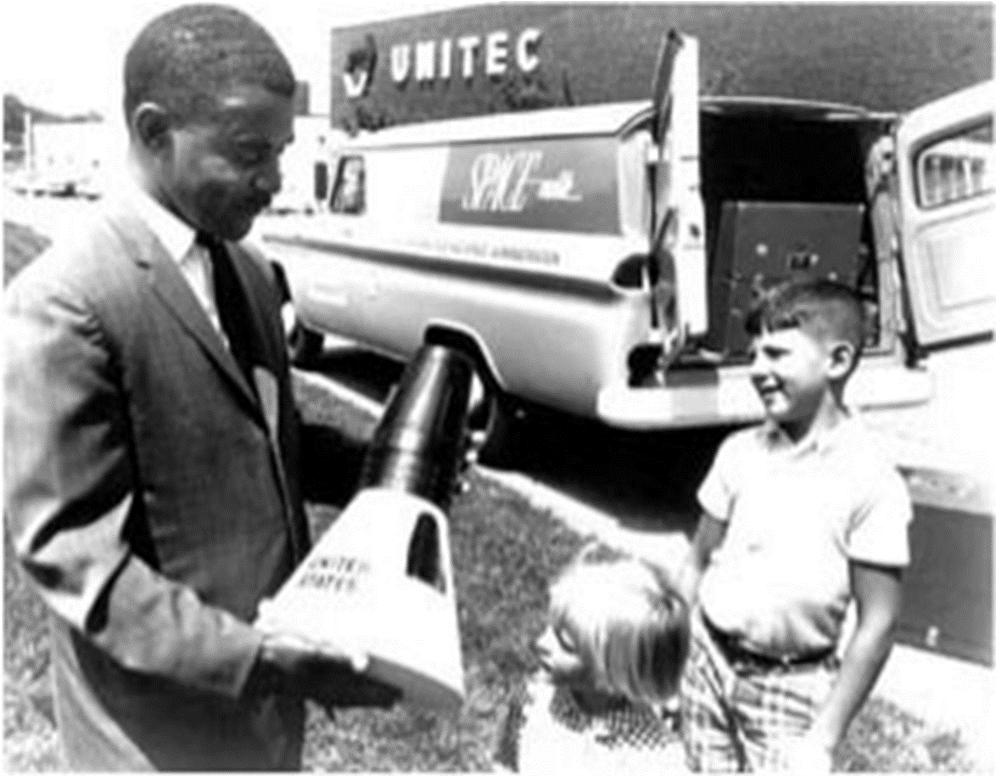

People, Artifacts, and Institutions

Here I provide a few documents and images that represent the way people, artifacts and institutions worked together in or near the Spacemobile program to generate, share and maintain specific knowledge about outer space with students and teachers in the early 1960s.

Documents

“Science Education in the Space Age”, Conference Proceedings, Los Angeles, June 1964. The conference brought the NASA Education Division, the U.S. Department of Education, the Department of Education’s State Science Supervisors and the American Association for the Advancement of Science together for a week to determine how best to include NASA’s offerings in science education.

“Teaching to Meet the Challenges of the Space Age” A Handbook in Aerospace Education for Elementary School Teachers from 1963. This is a curricular product of collaboration between the NASA Education Division, the New York Board of Education, and public school teachers in the Bronx.

“Aerospace Curriculum Resource Guide” from the Massachusetts Department of Education in cooperation with NASA. This is a comprehensive education plan for teaching space science and training teachers. Note on page viii the Advisory Committee and Education Consultants involved, on page ix the NASA resource personnel and the chapter Writers. Note also the Appendix listing which refers to Teacher Training. Sample schedules and topics for institutes and workshops are provided in the Appendix.

Images