Posted by Christina Roberts on June 9, 2021

Educating is Communicating

The academic field of Science Communications formed at the end of the twentieth century when researchers began to focus on how science learning happened in informal settings. Science educators, science museum professionals, science journalists, and communications researchers realized that they shared similar concerns about how to improve and increase scientific literacy, also referred to as the public understanding of science; they acknowledged that disciplinary boundaries and professional practices had long separated them.1 Science Communications could be more interdisciplinary if it included a historical perspective of the development of science communications in all its forms, including science education.

With this blog post I provide a historical view of the early years of space science communication to K-12 students during the first decade of the space age. Obviously educators in the past did not have the same principles devised by present-day Science Communications scholars. However, a brief review of early space science education shows that some of these fundamentals, as they were expressed in the pedagogy of the 1960s, were deployed in classrooms across the country. Here, I will highlight how early space science educators cared very much about Audience, Purpose, and Tone and how they used visual, auditory and tactile learning methods, what science communicators term Multimodal Learning, in their classrooms. My example is from a collaborative curriculum project between the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) the Lincoln Nebraska School District in 1966. 2

Audience, Purpose and Tone

Present-day science communicators prepare materials with their audience in mind. Their presentation of scientific research, facts and principles depends on whether their audience is made of laypersons, professionals or experts, or some combination thereof. Science communicators also consider the purpose of their presentation, such as if it is to inform, educate, warn, persuade or present an argument to their audience. Finally, the tone of their presentation aligns with audience and purpose, in that they choose a communication style such as playful, academic, businesslike, humorous, cautious or creative. 3

Science educators of the 1960s displayed similar concerns, as expressed in their curricular handbooks. The Lincoln Plan is a “Space Handbook” created for grade K through 6 teachers. The lesson plans are oriented towards maturity levels and not strictly by grade level, which shows how sensitive science educators were to their intended audience. The educators could choose to mix and match content and activities from different maturity levels to suit student needs in their individual classrooms. The handbook contains many pictures of teachers and students participating in space science lessons.

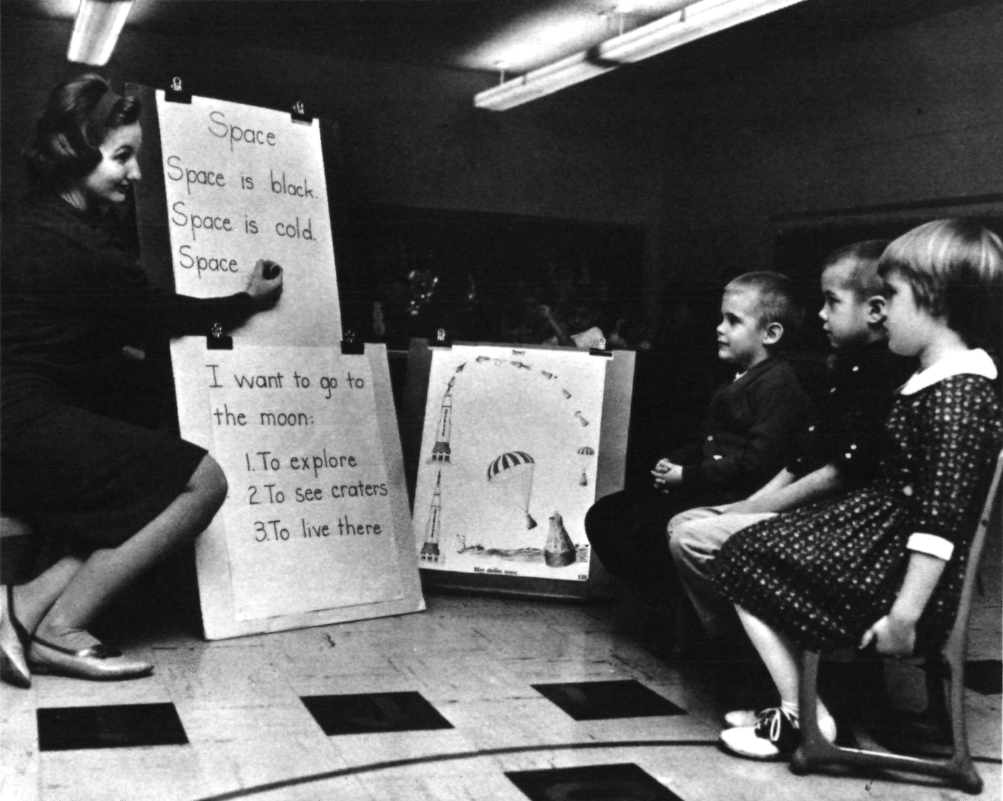

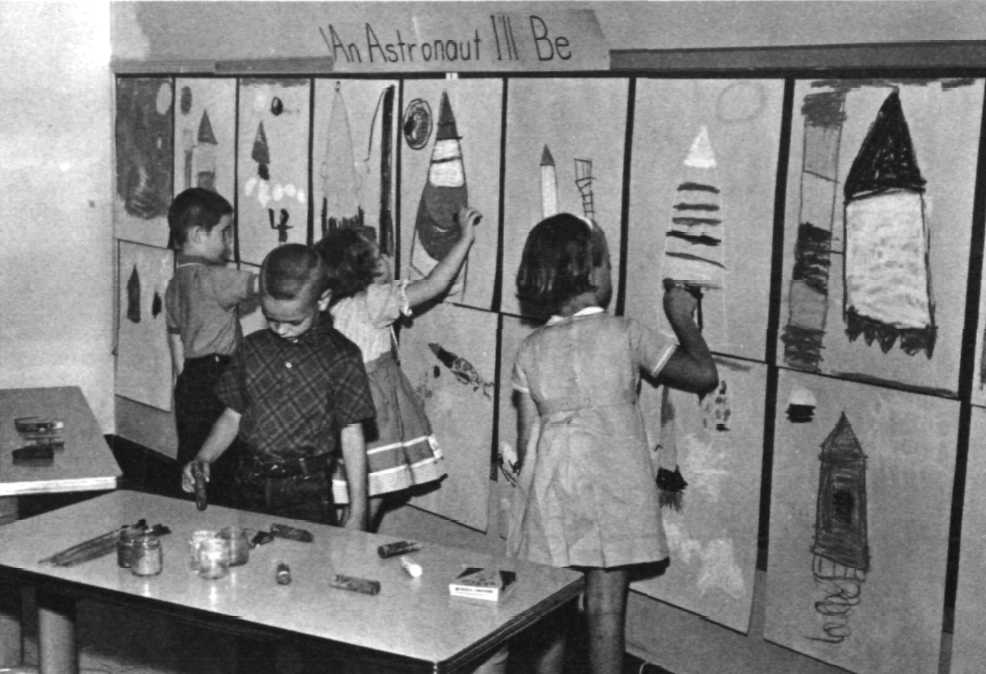

The handbook contains lessons organized by three categories. The teacher is provided with Instructional Materials, such as books, pamphlets, brochures, and kits, from which to choose information in specific Content Areas, and suggested Activities for student learning. For example, for the year five maturity level, teachers could choose content from Art, Language Arts, Arithmetic or Music to help students make connections to space science concepts. Optional activities such as drawing and painting pictures of rockets, counting down rocket launches, constructing rockets made from blocks, or creating a word/picture dictionary of space terms were all designed for the year five maturity level.

The purpose of the various content areas was to make scientific principles visible and understandable to students across the content areas of the curriculum. This would give students the opportunity to learn about space in a way that suited their interests, learning styles and personal capacities. The lessons are conveyed in an informative, calm and scholarly tone, but also provide an outlet for student excitement in the Activities category of Dramatic Play. For example, children could act out taking a trip to the moon or create and wear a space suit. The tone of the lessons indicates to students that it is appropriate and fun to learn about outer space and teaches them that the scientific principles of space exploration are personally meaningful, such as inspiring them to dream about being an astronaut when they grow up.

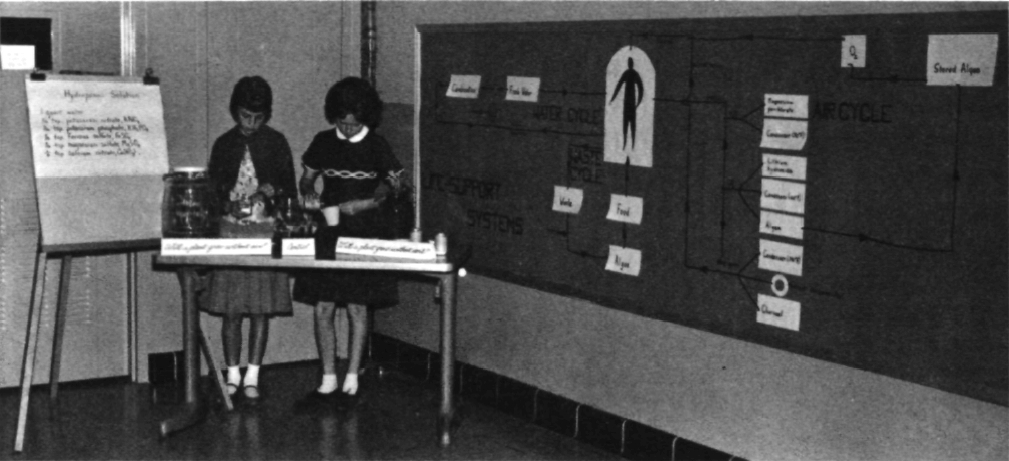

Space science educators adjusted their materials for different maturity levels. At the year eleven maturity level, the Content Areas and Activities in The Lincoln Plan handbook are more sophisticated, which corresponds to the skills, interests and capacities of a more mature audience. Students at this maturity level are instructed in Science, Health and Social Studies in addition to Art, Language Arts, and Arithmetic. The purpose of the handbook remains focused on providing connections to space science information and principles broadly across the curriculum, but prompts students to consider not only their own relationship to outer space, but the role and purpose of the U.S. space program in world affairs. For instance, students debate the wisdom of spending money on space travel research.

The tone of the lesson plans conveys the sense that space science is more challenging than entertaining, and the tone remains scholarly and calm while it promotes the potentially dramatic outcomes of space travel for humanity. One lesson asks students to research and report on the dangers of space travel; another to scientifically demonstrate the difficulties of hitting a moving target from a moving object. These activities help students at a higher maturity level realize that the space age is not only personally significant, but that they can help solve scientific challenges related to an entirely new human endeavor.

Multimodal Learning

Science communicators convey scientific information in visual, auditory and tactile modalities that stimulate human learning. They design interactive programs that teach scientific principles through touching or tinkering along with traditional visual and auditory channels. Multimodal learning helps students synthesize knowledge, leverage their learning abilities, and facilitates problem solving.3

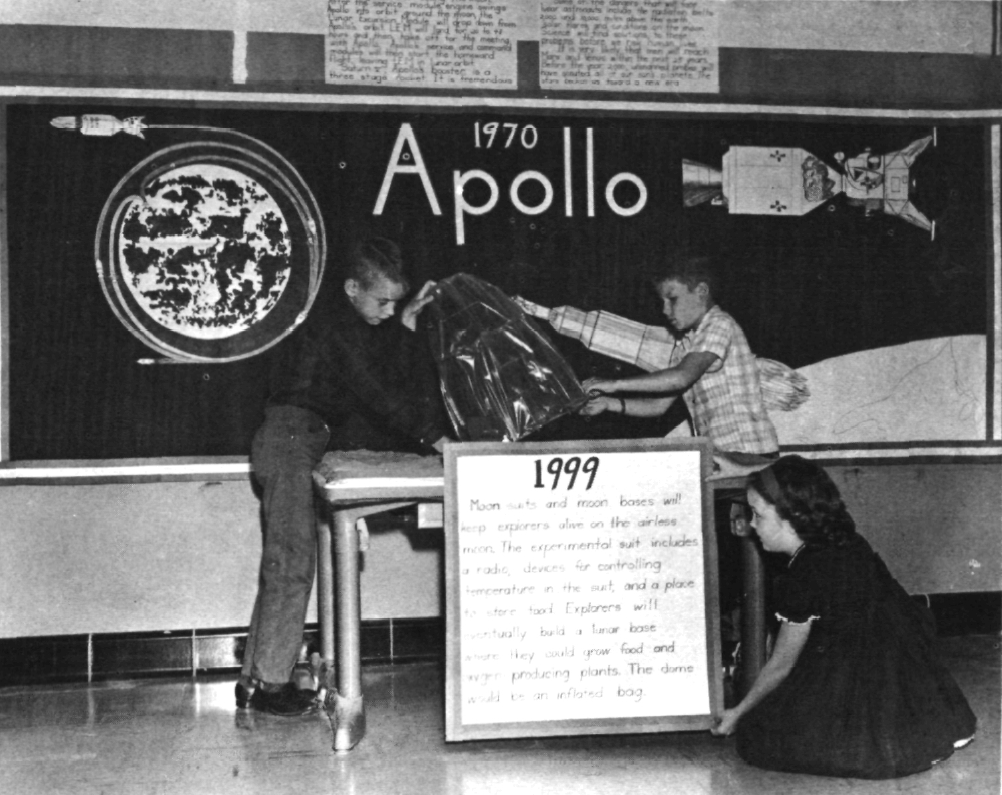

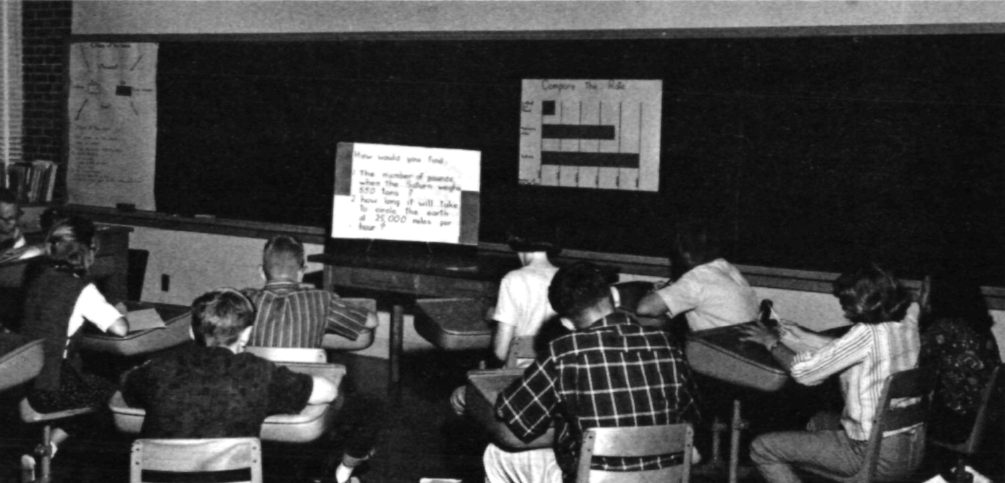

There are historical examples of science educators from the 1960s using similar methods in The Lincoln Plan space science handbook. We’ve already shown that students observe and listen to a teacher write space-related definitions on a large paper pad. They draw and paint rockets. Year six maturity level students could listen to music as they pretend to be rockets zooming to space. They could taste food that has been prepared and then blended together and squeezed through a bag to simulate eating like an astronaut. They could conduct experiments that teach that gravity is not needed to swallow, such as eating a cracker while standing on their head or drinking milk through a straw while upside down. Children at year 8 maturity level could build informational displays about the Apollo program with models they constructed and give oral reports based on news stories and classroom sources that they reviewed. Students at year 11 maturity level could use mathematics to study aerospace principles and calculate things like ground speed for an aircraft dealing with various head and tail winds.

This brief review of space science education from the 1960s for grades K-6 shows that the methods and modalities that science communications professionals rely on were used in an early form during the 1960s. Science communications also take place in the formal education setting and a more interdisciplinary approach to the field could be improved by including a historical approach to science communication in all of its many forms.

References

1 Lincoln Nebraska Public Schools. (1966). Introducing Children to Space. The Lincoln Plan. U.S. Government Printing Office.

2 Lewenstein, B. V. (2015). Identifying what matters: Science education, science communication, and democracy. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(2), 253-262. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21201. 253-254.

3 Bradley, Norman Douglas, “Doug” Lecture. UCSB. April 8, 2021.

4 Bradley, Norman Douglas, “Doug”. Lecture. UCSB. April 22, 2021.