Posted on December 14, 2020 by Christina Roberts

Robust Networks Emerge

I begin excavating Knowledge Infrastructures (KIs) in the history of NASA’s science education program by reviewing a week-long conference held in Los Angeles in June, 1964. The conference, “Science Education in the Space Age” was sponsored by NASA in cooperation with the U.S. Office of Education (USOE) and was hosted by NASA’s Western Operations Office. The committee in charge of the conference included representatives from NASA, the USOE and their Council of State Science Supervisors, members of the Subcommittee on Institutes and Conferences of the American Association for the Advancement of Science Cooperative Committee on the Teaching of Science and Mathematics (AAAS), and of course, many of the educators employed as Spacemobilers.

The conferenced allowed attendees to establish relations and build mutual assistance in space science education and to learn about emerging science education problems. The State Science Supervisors learned about NASA’s objectives, programs and educational services. NASA personnel and Spacemobile educators learned what the formal educators thought it was appropriate for them to undertake in science education. The different groups proposed a collaborative environment in which to configure NASA”s role in teaching space science. They supported NASA’s effort to improve and increase the public understanding of science overall.

By 1964, several of the NASA field centers began regional coordination of the Spacemobile program in concert with the Department of Education’s State Science Officers. There were also contractor companies who managed the Spacemobile program after the Franklin Institute’s inaugural year. The contractor companies hired, trained, and deployed the Spacemobilers to communities often suggested by the State Science Officers. Educational Services Corp., a Washington, D.C. company, took over from the Franklin Institute in 1962, and Unitec Corporation from Maryland took over in 1965/1966 until the the Spacemobile contract was awarded to Oklahoma State University beginning in 1968. The Spacemobile contract remained with Oklahoma State University for several decades, with a brief interlude in the 1970s at Chico State University in California. The Spacemobile employees were contractors, not government employees.

It is apparent that there were robust networks of people, artifacts, and institutions functioning along with the nascent Education Division. They crossed institutional boundaries to mutually generate, share and maintain scientific knowledge about outer space. The 1964 conference is where individuals, established science popularizers and federal organizations came together. The subsequent reorganization and focus of NASA’s education program shows that they were willing to adapt routines and shared norms and practices to mutually improve science education.

Co-Production

The 1964 conference discourse shows that science education stakeholders reacted to the pressures of the space age by promoting and maintaining a scientifically-oriented society. We learn about the motivations, values and world view of the NASA Educational Division administrators who perceived that the space age accelerated educational problems, but also provided opportunities for improvement. The popularity of the space program maximized the so-called mid-century knowledge revolution. Administrators touted the economic benefits of higher education to justify NASA’s interest in space science education.

The Education Division understood that space science was popular. They intended to merge popularization efforts with formal and informal education to improve the general state of science education and to increase the status of space science in the American school system. They believed that the developing space age had social repercussions that required well-educated students to play their part in a rapidly changing world.

Co-production is a Science and Technology Studies (STS) theory that investigates and formulates how scientific knowledge “embeds and is embedded in social practices, identities, norms, conventions, discourses, instruments and institutions.” (Jasanoff, 2004). There are four site of co-production referenced by Jasanoff that are also represented in the Spacemobile program. Educators of all types were involved in “making identities, making institutions, making discourses, and making representations.” I suggest that the NASA Education Division wanted to create scientifically trained students and teachers (identities), raise the stature of NASA and the division itself (institutions), create social discourses about the relevance of space science, and represent NASA as the educational authority for all things related to space.

Demonstration

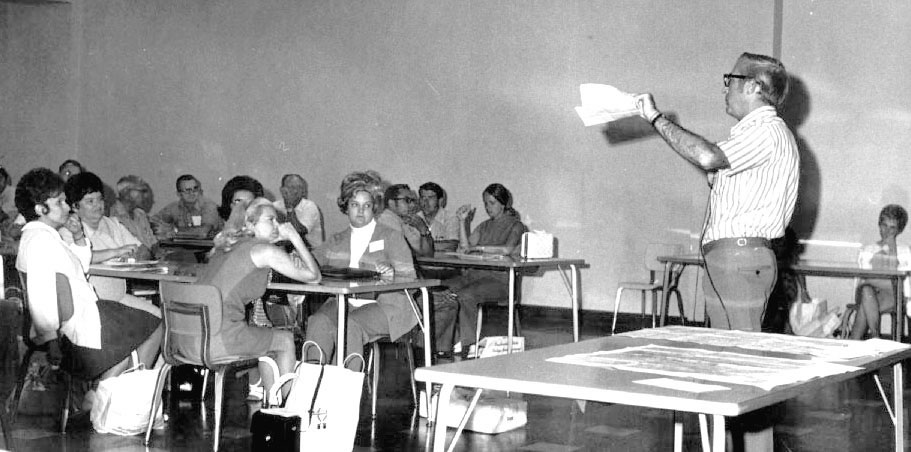

Lecture-demonstrations were the main event of each Spacemobile visit, as well as a vital part of teacher training workshops and summer institutes.

In Science and Technology Studies, demonstrations are one of the tools of the co-production of scientific and social orders. Sociologist Claude Rosental studies how democracies use public demonstrations to manage public affairs. He explains that demos (a certain type of demonstration) are used across many domains in economic life, politics and science and technology. Demos induce people to make investments, purchase products, and support public spending. Demonstrations have rhetorical power in their materiality and are viewed as sources of credibility and persuasion. They are also spectacles and entertainment, and performances that teach viewers and provide evidence. Demonstrations exhibit technological devices or conduct experiments in front of an audience. The demonstrator usually follows a script to show that the science or technology is feasible or valuable. Demonstrations also show that public spending produces results. (Rosental, 2013). The lecture-demonstrations conducted by the Spacemobile educators had all of these features.

In fact, the Spacemobile program pre-dates Rosental’s discussion of NASA’s later online public demonstration of the Alpha project, a collaborative software program. He explains that the Alpha demos attempted to build credit with the public and the educational community after the Challenger disaster. The project used demos, lesson plans, and educational software to increase public support for the agency. Rosental notes that “using demos for educational purposes induces specific relationships between the public…and science and technology institutions like NASA…”. My research about Spacemobile shows that NASA already had this kind of experience in the analog world. They relied on public demonstrations to build and create relationships through the Spacemobile program for at least two decades prior to doing it online.

The Stack

Recall sociologist Benjamin Bratton’s research about the internet Stack. He views stacks as a kind of platform of interoperable layers with generic, extensible and pliable properties that provide modular recombinancy within synthetic planes (52). Bratton describes platforms as generative mechanisms that set terms of participation through fixed protocols. They grow and strengthen by mediating unplanned interactions. They can be technical or institutional models. (44). The platform-as-stack instructs my thinking about how NASA interacted with so many layers of public science education.

NASA’s interoperable layers meant that it could recombine as needed into a new form of science educator. As noted in the first blog, NASA was also a science popularizer at public events and on television and radio. The Education Division also generated participation through fixed protocols such as auditorium lectures, teacher training workshops, and summer conferences. It generated activity beyond its own synthetic lecture-circuit planes to enroll state boards of education, school districts and educators into curriculum production projects that sometimes took several years to reach fruition.

Bratton suggests that actors are drawn into a common infrastructure by a simultaneously centralized and decentralized platform that distributes autonomy at the edges of its network, while standardizing conditions of communication from center to periphery. (46), NASA is easily considered a platform because of its “cultural, political, and economic” function in American life. It was historically central to the development of the space age, and tried to standardize space science pedagogy. The agency’s role in the education system was masked by the autonomy it provided to its educational network, to whom it seamlessly provided supplemental science curriculum resources and pedagogical training. NASA positioned itself neutrally as an assistant to formal public education. Bratton notes that platforms are often “formally neutral” but retain their own ideological strategies for organizing their publics.

Aerospace Education Services Program (AESP) Archive.

In fact, the Education Division really claimed to be neutral at the 1964 conference. Frederick Tuttle, the Deputy Director of the Educational Programs Division, said “We have no point of view to espouse, no bill of goods to sell.” Rather, he said that all the members of the conference committee had “one all-embracing purpose” to lead all of the participants to “a greater understanding of space science developments and of space science education, Grades 1 through 16.”

This brief excavation of the Knowledge Infrastructures (KIs) of NASA’s historical Spacemobile shows that the concepts of co-production, the sociology of public demonstration and the stack are productive research tools in the history of science education.

References

“Mission And History”. 2020. American Association For The Advancement Of Science. https://www.aaas.org/mission.

Bratton, Benjamin H. The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016.

“Council Of State Science Supervisors – History”. 2020. Cosss.Org. http://cosss.org/history.

Jasanoff, Sheila. “The Idiom of Co-Production.” In States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order. London: Routledge, 2004

Oklahoma State University College of Education. “Hall of Fame 2012. Dr. Kenneth J. Wiggins.” June 6, 2012. Youtube.Com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ELrgqWBGu6A&feature=youtu.be.

“OSU/NASA Education Projects: PDC Conferences”. 2020. Nasaweb.Nasa.Okstate.Edu. http://nasaweb.nasa.okstate.edu/AESP_40th

Messer, Todd and Steve Garber, and SA 10.08.04. 2020. “Challenger STS 51-L Accident January 28, 1986”. History.Nasa.Gov. https://history.nasa.gov/sts51l.html.

Rosental, Claude. “Toward a Sociology of Public Demonstrations.” Sociological Theory 31, no. 4 (2013), 343-365. doi:10.1177/0735275113513454